Dan Schulz, Badger Bates, Anne Poelina, Sarah Martin & R. Quentin Grafton

The world is at a crossroads and desperately needs pathways towards a safer and more just water future. Climate change; the need for rising food production; rapidly rising incomes that increase water consumption; water governance failures; and inequality (especially water access and influence with decision-makers) are contributing on-going declines of the world’s rivers. Here, on World Rivers Day, a group of researchers, artists, and Traditional Owners have come together to share their collective wisdom of two Australian river systems, Baaka & Martuwarra.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Baaka River system

Baaka (also known as the Darling River) is located in far western New South Wales in south-eastern Australia. It was once an oasis of new and old river channels, anabranches, creeks, large shallow lakes, billabongs, swamps, and springs coming up from underground. For the Barkandji (people of the Baaka) this place provided everything: fresh water, fish, yabbies, shrimps, mussels, turtles, birds and birds’ eggs, seeds to grind, starchy tubers and yams, nuts, fruit and, in winter, greens were everywhere.

Barkandji never left their Country, they are still there, and they love their Country, and it loves them back. Barkandji created many in-stream, stone-walled fish traps that harvested part of the mass migrations of fish during spring and summer floods. They also managed the movement of water back into the river channel through wooden and earthen weirs, fish traps and fish nurseries; and this provided temporary rich and diverse habitats.

Modern-day Baaka’s tributaries are heavily controlled in terms of their stream flows with weirs and dams. Increased upstream extractions have reduced Baaka’s stream flows at an accelerated rate over the past 20 years (see Fig 1). These water extractions run counter to the rights of Indigenous peoples across the region and impose big costs on Indigenous peoples’ way of life.

Figure 1: ‘Water as Life: The town of Wilcannia and the Darling/Baaka 20 August 2007’ by Ruby Davies. The image portrays the consequences of a water extraction on the people and landscape during the Millenium Drought. (From Bates et al, 2003.)

The Barkandji have seen the in-river infrastructure they used to enhance Baaka’s habitats, destroyed during the colonial period. Their structures were destroyed in an effort to improve river navigation. The Barkandji witnessed the catfish die, with silver perch and mussels now disappearing, while the river snail disappeared years ago. They are now observing the decline and disappearance of birds, water spiders, river boatmen, water rats and water lizards, while river plants and floodplain plants are dying.

Despite their deep and multi-millennial connections to Baaka, the Barkindji have very limited legal water rights over their sacred river. The Barkindji, along with other native title holders including the Ngiyampaa, Ngemba and Murrawari peoples, continue to suffer from a situation where non-Indigenous water users hold the power to access these highly valuable water resources (and the benefits that flow from this), while power and agency for Aboriginal peoples remains obstructed.

“What happens when big companies come out and they do a lot of irrigation, take the water from the rivers and that. All the fish had died. It was here. Because right across Baaka, they built a big wall, but the fish was trapped because they couldn’t move.”

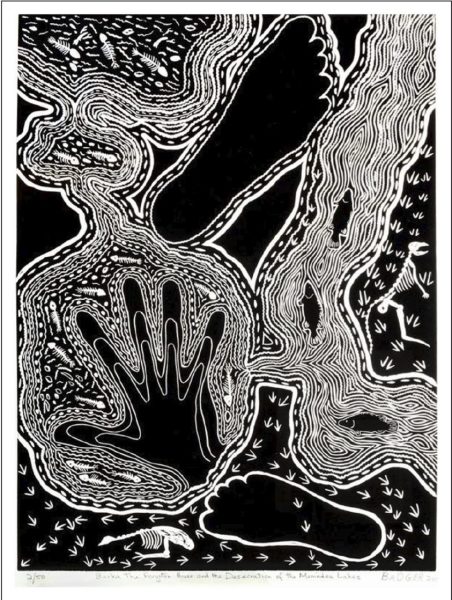

These are the words of ‘Badger’ Bates, first author of the paper ‘A Tale of Two Rivers’, and they are visualised in the wrinkly marks that indicate the lakes are drying up and the fish are dying, with the three Murray cod in the weir pool, while the rest of the river is drying (Bates et al, 2023).

Figure 2: ‘Barka The Forgotten River and the Desecration of the Menindee Lakes’, by Badger Bates 2018 (From Bates et al, 2023).

The handprints are three generations of the artist’s grandmother’s family, and the footprints of two generations (Fig 2). In the words of the artist:

‘These prints mark our belonging to this land and water, and we are saying stop this desecration now. White people and black people sobbed and cried for the loss of a way of life that had sustained Barkandji for many thousands of years’.

In March 2023, after record floods in the Murray-Darling Basin, and only four years after the previous mass fish kill at Menindee in 2018/2019, as floodwaters receded, there was another mass fish kill. This time it was caused by hypoxic blackwater. Yet water agencies in the immediate days after this death told the Menindee community that this was a ‘natural event’.

Martuwarra River system

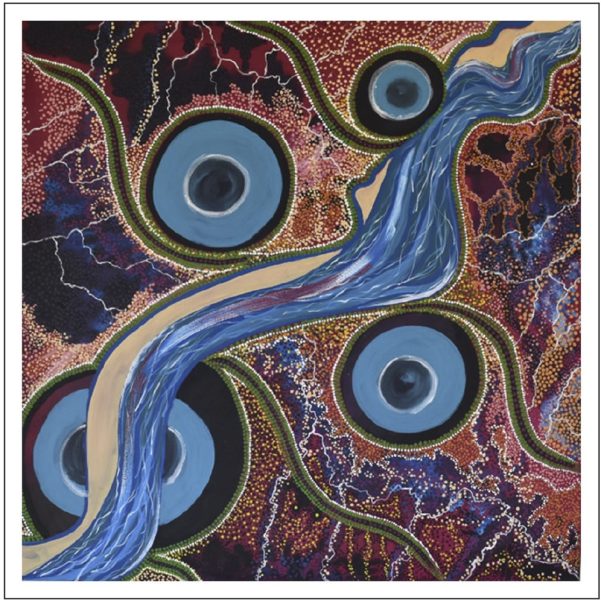

Martuwarra, also known as the Fitzroy River and located in the Kimberley region of northwestern Australia, is central to life of its Traditional Custodians. It is a world of abundance with ducks, fish, meats and all types of bushfood, including home to threatened species. Since Bookarrarra, the beginning of time, Martuwarra nations have co-existed as one society in peace and harmony while managing their living land, water and people systems under Warloongarriy Law (First Law). This is a law of obligation to protect Martuwarra across the circle of time; past, present, and future (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ‘Spirit of Martuwarra’ by Hozaus Claire (2022). Hozaus Claire’s painting, ‘Spirit of Martuwarra’ is his expression of his connection to land and water, especially the Spirit of water. The perspective is from a bird’s eye; the water brings and keeps everyone together and shows how all animals and people are connected spiritually. The story is in the ground and on the land to which First Nations speak. (From Bates et al, 2003.)

Today, water management of Martuwarra, in terms of ‘who gets what and when’, has little input from Aboriginal Traditional Owners. Decision-making authority lies with the Western Australian Minister for Water with comments by Traditional Owners on water licenses only needing to be ‘considered’ by the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation. There is no legal mechanism for joint decision-making.

Six First Nations of Martuwarra established the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council in 2018 as a direct outcome of the 2016 Fitzroy River Declaration, when Traditional Owners agreed to maintain Warloongarriy, First Law. The Declaration sought to promote ‘inclusive collaborative long-term planning, and sustainable development that incorporates the ongoing needs of humans, the environment and culture.’

Elders of First Nations along Martuwarra, through their films and publications, have championed cultural values and water ethics through ‘Living Waters’, First Law, Indigenous sciences, and water governance from the oldest water guardians.

A Weaving of stories

Since 2020, Baaka and Martuwarra have been in an ongoing conversation to connect Traditional storytelling between the two river systems because of their cultural and ecological importance. In 2022, a coalition of multi-disciplinary academics, artists and Traditional Owners came together to write about and discuss the story of these two rivers, and to respond to the costs of inaction. The paper ‘A Tale of Two Rivers’ was one outcome of that meeting.

A Tale of Two Rivers tells the story of Baaka and Martuwarra in multiple ways and across different knowledges. It tells of two rivers, guided by Traditional Owners, and pathways to restoring and to protecting these ancient systems, as well as to respond to water injustices of the Baaka and Martuwarra.

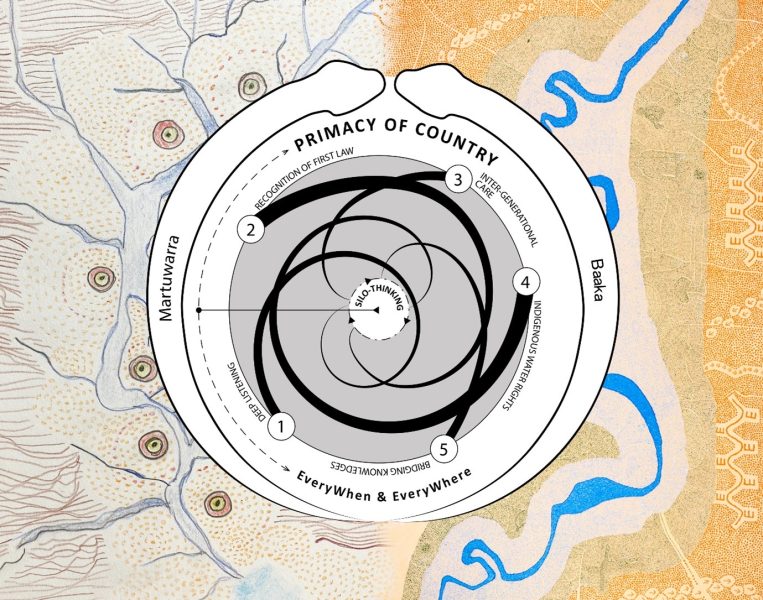

This dialogue sought to shift water management away from what the authors call ‘silo-thinking’, which is the present condition of water governance being applied to these systems. This approach sees the rivers as resources for extraction rather than living systems. The two river systems are represented as connected Rainbow Serpents, one for each river system, which encompasses the Primacy of Country. Through multiple and emergent journeys toward the Primacy of Country we move away from ‘silo-thinking.’ These five journeys, although not exhaustive, are all necessary, and include: 1) Deep Listening; 2) Recognition of First Law and Custodianship; 3) Intergenerational Care that links the past to the present and to the future; 4) Indigenous Water Rights; and 5) Bringing Together Different Knowledges (Fig 4).

Figure 4: Flows of Water Justice. (Artwork supplied by Glenn Loughrey and final design by Dan Schulz. From Bates et al, 2003.)

Deep Listening is a human process, and something the authors seek to do in their work, art, and life. It includes connecting to and spending time on Country with Traditional Owners. Deep listening requires decision-makers to listen to Country, is learned and requires the guidance of Traditional Owners.

First Law is the law of the land and living water systems. It is upheld through stories, song, dance, and ceremony. Recognition of First Law and Custodianship is the adoption and implementation of Indigenous water governance principles, which dictates the primacy of cultural, environmental, and sustainable outcomes over water extractions (other than for critical human and non-human needs such as town water supplies or stock and domestic use). Water planning should specifically include First Nations and explicitly account for their values, including cultural values and ‘Caring for Country,’ as is outlined by the specific protocols and needs of each First Nation in the water catchment.

Intergenerational Care links the past to the present and to the future. It implies long-term thinking and sustaining the health of Country for future generations, as First Nations people have done for millennia on Baaka and Martuwarra. It dictates that water allocations be based on the precautionary principle and that climate change, using the best available science, should be considered in water planning. Intergenerational care also considers the impacts of development on groundwater (and their interconnection with surface water), as groundwater health can impact the long-term sustainability of surface water and the ecosystems that are supported by river flows.

Indigenous water rights are the rights that Indigenous peoples have to their waters (and lands) as per the human rights standards described in the United Nations Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples.

Bringing together knowledges, as participants in ‘A Tale of Two Rivers’ sought to do, is the meaningful engagement with river-based communities, especially Indigenous peoples. This transcends commonly accepted perceptions of knowledge and includes art as a way to journey from the literal to the imaginative and across the senses; from listening to seeing; a holistic of way of understanding.

In our collective view, the living water of rivers connects us all. It inspires respect, responsibility, and reciprocity. Rivers holds dreaming stories, song lines, law, and knowledge. Our telling of a Tale of Two Rivers communicates our shared understanding by both word and art under the guidance of Traditional knowledge holders. It’s a story worth listening to.

Key Reference

Bates WB (Badger), L Chu, H Claire, MJ Colloff, R Cotton, R Davies, L Larsen, G Loughrey, A Manero, V Marshall, S Martin, N-M Nguyen, W Nikolakis, A Poelina, D Schulz, KS Taylor, J Williams, P Wyrwoll & RQ Grafton (2023). A tale of two rivers – Baaka and Martuwarra, Australia: Shared voices and art towards water justice. Published 18 July 2023 in The Anthropocene Review, https://doi.org/10.1177/20530196231186962

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dan Schulz is a PhD student at the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy. He is a resident of Broken Hill in NSW. Dan’s research looks at the past 30 years of water policy and management in relation to the Darling-Baaka River and Menindee Lakes. Dan is a visual artist, filmmaker, and co-creator of Water Watch Radio at Broken Hill’s community radio station, 2DRY FM. For more information on the research practice of Dan Schulz visit Fluid Fronts and Water Watch Radio.

Badger Bates was born on the Baaka (Darling River) at Wilcannia in 1947. He was brought up by his extended family and his grandmother Granny Moysey, learning from them the language, history and culture of the Barkandji people. He continues travelling the country looking after important places and teaching young people about their culture and their country. Badger is an artist, cultural heritage consultant and environmental activist. His art shows his connection to Country and the complex relationships between people, country and water. Recent exhibitions include Art Gallery of South Australia’s Tarnanthi festival 2019, the Biennale of Sydney Rivus 2022, and The Australian Museum ‘Barka the Forgotten River’ 2023.

Anne Poelina is the Co-Chair Indigenous Studies and Senior Researcher at the Nulungu Institute Research University of Notre Dame. She’s a Kimberley, Nyikina Warrwa Indigenous woman and Chair, Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council.

Sarah Martin is a heritage professional and archaeologist working with Indigenous communities to create multi-layered histories of the semi-arid regions of New South Wales by combining archaeology, archival records and oral history. Research interests include black earth mounds on the Murrumbidgee riverine plain, as indicators of a mid to late Holocene focus on managed, dense, predictable, carbohydrate-rich plant crops and their prolonged cooking in heat retainer ovens to maximise carbohydrate returns. She is currently working with Indigenous community members communicating relationships with country and waters through art, archival and oral history, in response to the degradation of the river systems.

R. Quentin Grafton is Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU, Convenor of the Water Justice Hub, and Executive Editor of the Global Water Forum.

The views expressed in this article belong to the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Global Water Forum, the UNESCO Chair in Water Economics and Transboundary Water Governance, UNESCO, the Australian National University, Oxford University, or any of the institutions to which the authors are associated. Please see the Global Water Forum terms and conditions here.

Banner image: The river runs dry. Like many Australian rivers, the Baaka and its tributaries often run dry; but over-regulation and over-extraction of the Baaka’s water in recent decades has seen this river drier and for longer, resulting in a profound decline in the biodiversity and ecological health of the system. Non-Indigenous water users hold the power to access these highly valuable water resources, while power and agency for Aboriginal peoples remains obstructed. (Image by Dan Schulz)